Vapour Pressure Deficit – Understanding how Temperature and Humidity Affect Plant Growth

During the course of learning to grow, almost every gardener will discover that air temperature and humidity can have quite an effect on their plants. This is called Vapour Pressure Deficit. In this article, we will be taking a good look at this very interesting and important topic. A good understanding of how temperature and humidity affect plant growth can give a gardener a real advantage in optimising their growing environment. And their plants will be all the happier (and more productive!) for it.

Explaining the term: “Vapour Pressure Deficit”

Vapour Pressure Deficit (VPD) is basically the drying ability of the air.

Moisture in the air causes a sort of pressure which bears down on the plants. This type of pressure is somewhat different to the normal concept of pressure.

High air temperatures and low humidity are a combination that will cause moisture in or on something to dry more quickly than in cooler and higher humidity conditions. Also, air movement increases the drying ability of air. A more scientific definition is that VPD is the difference between the amount of moisture in the air and the amount of moisture the air can hold when saturated.

Rot and Mould

The combination of both humidity and temperature has a direct effect on two very important aspects of gardening. The first of these is something called plant transpiration. The second is dew point and the and how that can elevate the risk of fungal attacks (ie rot or mould).

Plant Transpiration & Stomata

First of all, let’s take a look at plant transpiration. As most growers will already know, plants mostly obtain their water by drawing it in through their roots (although they can absorb it through their leaves when it rains). The water is then distributed through the plant via the stems and eventually to the leaves and flowers. On the underside of plant leaves there are microscopic “breathing” pores called stomata. The plant uses these stomata to absorb CO2 which is required for photosynthesis, and also uses them to release the oxygen which is created as a waste product. However, because the lining of the stomata need to be wet (in order to be able to absorb CO2 from the air), it means that it is through these stomata that a large proportion (up to 90%!) of a plant’s water loss occurs.

Because there is a cost for photosynthesizing to the plant in terms of water, the stomata of a plant have the ability to close when the cost would be too high. To keep plants as productive as possible, ideally the stomata would only close during the dark-period (or at night for outdoor plants) which is when the plant has no light to photosynthesise with, and so has no need to absorb CO2.

The stomata will begin to close if the plant begins to sense that the payoff of having the stomata open (in order to get CO2 which enables photosynthesis) is not worth the expenditure in water loss. This would usually be due to one or more environmental factors such as high air temperature, low humidity, the light level or CO2 concentration, and if the roots cannot find water. However, water loss cannot be prevented entirely and if the roots cannot find water then eventually the plant will wilt and possibly die.

The need to get the temperature & humidity combination right

Relative humidity is not the only factor that affects water loss through the stomata. It is the combination of relative humidity and temperature that actually determines this.

A combination of dry environmental air (low humidity) and warm temperature would cause water to be lost at a faster rate than it would in humid conditions. The plant recognises this as a problem and again will gradually close the stomata to conserve water. The closing of the stomata is a gradual process and they can be partially closed too. The amount that the stomata will close is somewhat relative to the level of risk of running into a water shortage.

The Role of CO2 in Vapour Pressure Deficit

As we mentioned a moment ago, plants need CO2 to photosynthesize. If the plant has shut its stomata in order to conserve water, then it is unable to absorb CO2 and photosynthesis slows or stops. If photosynthesis stops then the plant cannot create the sugars that it needs in order to grow. Obviously, we want our plants to keep their stomata open during light-periods to maximise photosynthesis. This is where knowing about Vapour Pressure Deficit is useful as it is a far more accurate way of predicting water loss and risk of fungal infections than by considering relative humidity alone.

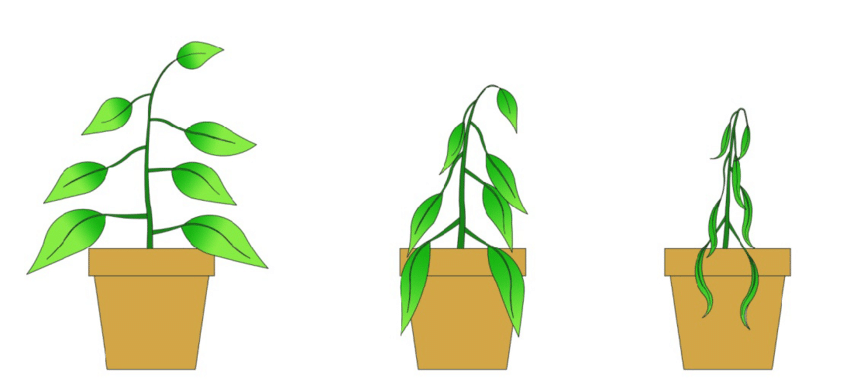

As VPD increases, the drying ability of air increases. Plants transpire more, requiring more water to be drawn in from the roots. However, as we have already mentioned, plants also know that to a certain extent they need to be careful with their precious resource – water. In most cases, a certain amount of VPD has a positive effect because the flow of water from the roots to the rest of the plants carries nutrients with it in this process called transpiration. However, if the VPD is too high, stomata will begin to close to reduce water loss and growth begins to slow down. Therefore it becomes clear that we need to keep the VPD in the correct zone (for the particular plant stage) in order to maximize growth.

Note the end of the last paragraph there: “for the particular plant stage”. This is important. Reducing water loss down to an absolute minimum is absolutely crucial for a cutting that has no or few roots. As we mentioned before, if the VPD is too high, the cutting will simply wilt and die. A propagator with a lid like the one below helps to keep VPD low until roots have developed.

The Importance of Transpiration in Vapour Pressure Deficit

At the opposite end of the scale, a consistently low VPD is not good either. A low VPD indicates that the air is holding a lot of water (relative to the total amount that can be held at that particular temperature). It means that the air has little “drying” ability. If the plant does not lose water through the leaves then transpiration is low.

If transpiration is low then very little water will be drawn up by the roots. When little water is drawn up through the roots then little nutrient will drawn up too, which could cause a deficiency in the plant. Low VPD also corresponds with a risk of mold. If you have ever battled molds, and experienced the devastation of botrytis and powdery mildew, then you’ll want to avoid low VPD like the plague.

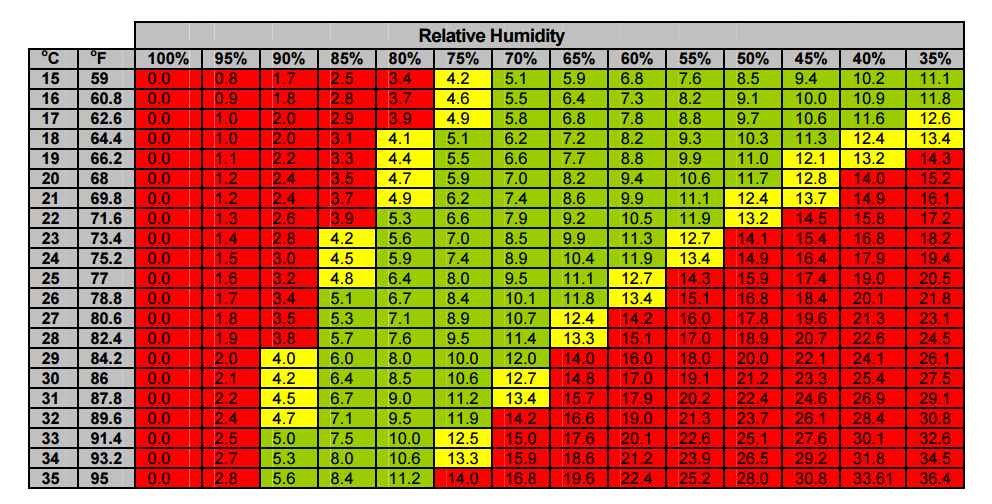

Here is a chart showing the VPD levels at different temperatures and RH levels For best results measure the leaf temperature with an infrared thermometer:

For good transpiration with low risk of mold it is best to try to keep the VPD in the green region and avoid the red regions.

Meters to Keep Vapour Pressure Deficit Under Control

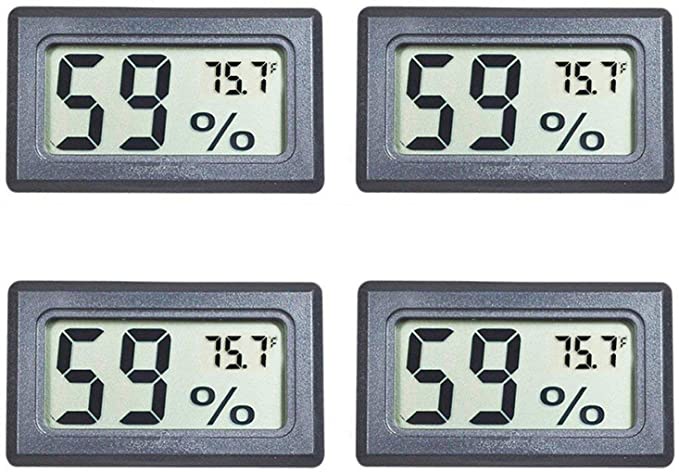

If you are growing a large number of plants in a confined space like a greenhouse or grow room, you will need temperature and humidity meters. Often these come in a single unit like these:

A CO2 Meter is also important for optimal plant growth:

Explaining Dew Point

The dew point is the temperature at which the air is saturated with water vapour, or in other words, the relative humidity is 100%. When this happens, the temperature only needs to cool a little more and the water vapour will start to condensate out of the air making things wet, particularly cold surfaces. At these humidity levels there is a huge risk of fungal infections not to mention, the plants can barely transpire and therefore grow. It is to be avoided at all costs.

The end conclusion of all of this is that the grow environment conditions (CO2 levels, temperature and humidity) is critical for a successful grow.

If you liked this post and would like to learn more, check this out: How to Prepare Water For Hydroponics – pH, TDS and ppm

Related Posts

Can You Profit From Hydroponics?

5 (8) Did you hear the story of a farmer who started growing strawberries? Yes? But, do you know he…

Conventional vs. Organic Hydroponic Nutrients

0 (0) Are “Organic” nutrients really better for your system or for your customers? Find out in this video from…